Vertical Structure of Ocean Eddies

Mesoscale eddies are swirling oceanic vortices with horizontal scales of 10s-100s of kilometers, evolving on time scales of days to months. These features occupy a disproportionately large role in setting the global ocean state and contain about 90% of the ocean’s kinetic energy. Mesoscale eddies modulate the ocean’s stratification, energetic pathways, and mixing/transport of physical and biogeochemical tracers such as heat, oxygen, carbon, and nutrients.

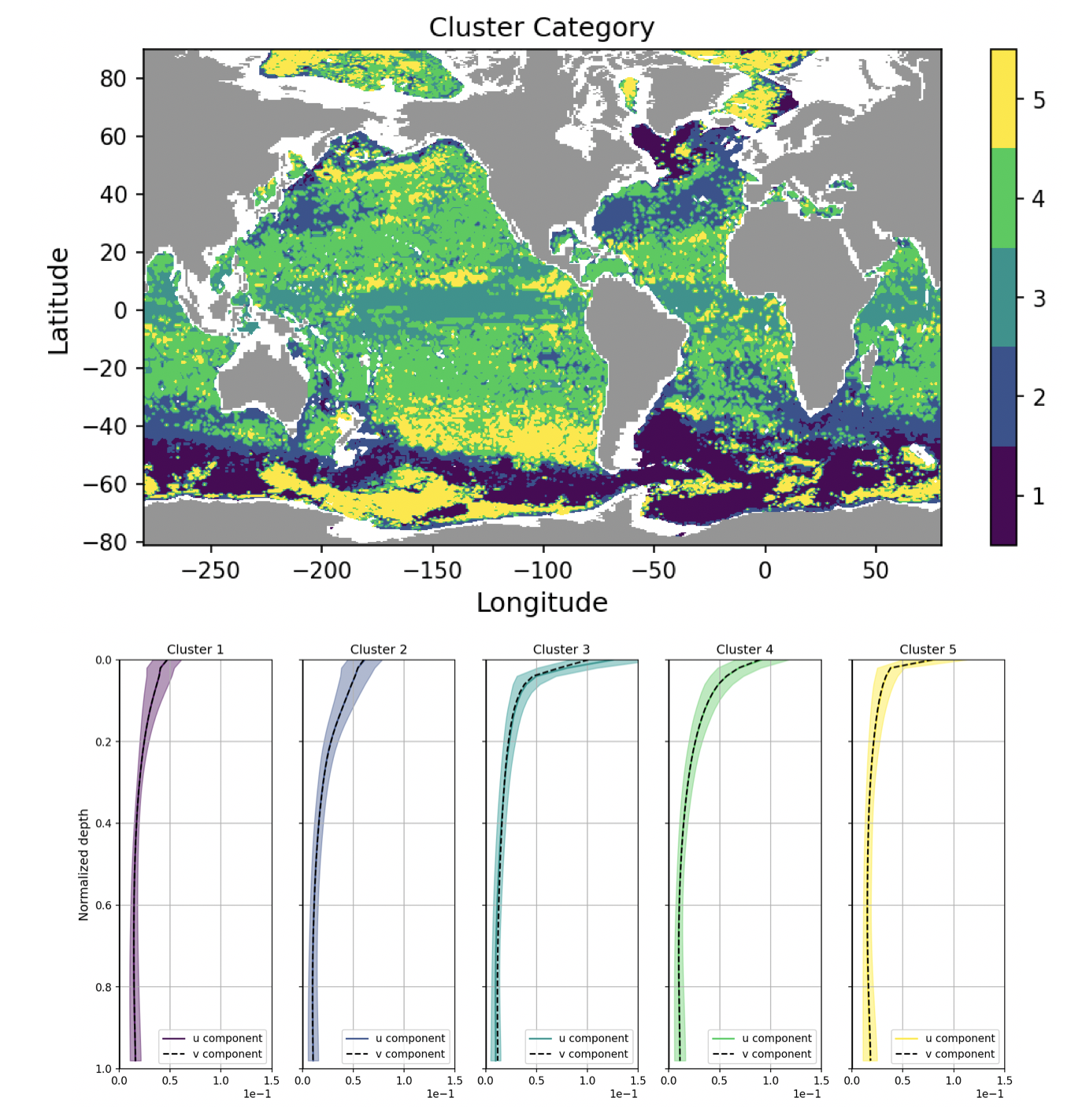

A characteristic of ocean eddies that is critical to predicting their influences on other physical and biogeochemical oceanic processes is their vertical structure. In some regions, eddies are strongly surface-intensified and their energy decays to zero below the uppermost few hundred meters of the water column. In other regimes, eddies are more barotropic (uniform with depth), and retain significant energy down to depths of 5-6 kilometers. I am interested in studying the factors governing eddy vertical structure regimes by applying a combination of idealized numerical modeling, analyzing high-resolution ocean models, and comparing model results to full-depth observations where available. Results of this work will allow us to incorporate vertical structure knowledge when parameterizing mesoscale eddies in coarser climate models, and allow us to infer deep ocean properties from surface measurements.

This work is part of the Ocean Transport and Eddy Energy Climate Process Team. A talk on eddy vertical structure that I presented virtually at the Ocean Sciences 2022 meeting may be found here.

Submesoscale Turbulence and Mixing

As technological developments allow us to observe and model increasingly finer-scale motions, the role of submesoscale phenomena emerges as critical to setting physical, chemical, and biological properties of the World Ocean. The submesoscale range of motion (lying below the mesoscale) has length scales of 100s-1000s of meters and time scales of hours to days. Whereas mesoscale motions are largely balanced and quasi two-dimensional, submesoscale motions mark the regime transition into unbalanced dynamics and three-dimensional turbulence. Submesoscale features include internal waves, inertial-convective instabilities, and surface mixed layer eddies.

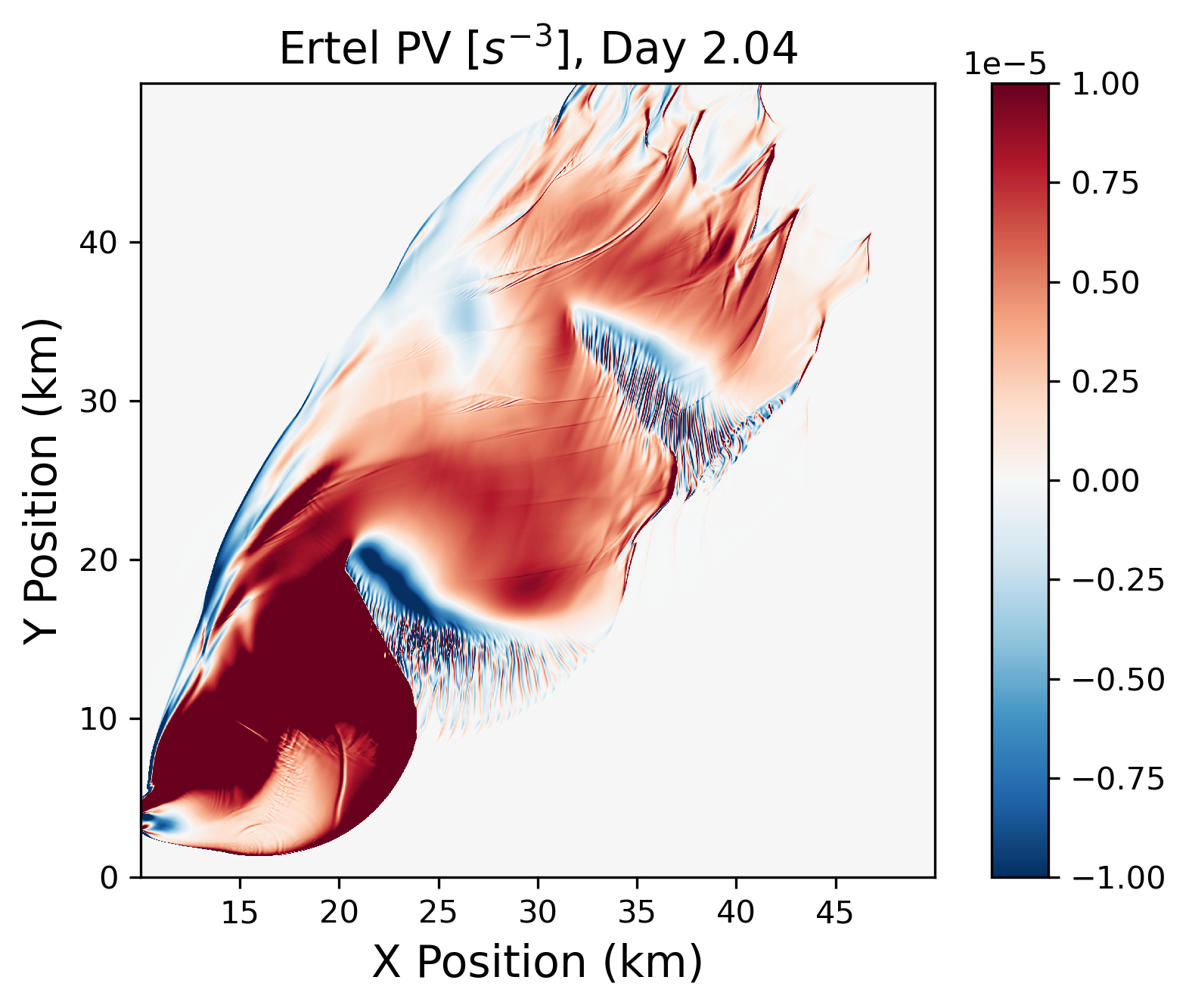

I am interested in a particular submesoscale process known as symmetric instability (SI), which is a hybrid between gravitional and inertial instability (where, respectively, gravity and the Coriolis force are the restoring forces). SI arises in frontal regions, near the surface, and in the bottom boundary layer. Whereas many prior works have focused on studying near-surface SI, my work has emphasized the prevalence of SI in near-bottom flows. In particular, I found SI to be the dominant mechanism leading to turbulent mixing in Arctic dense gravity currents. More recently, I have also studied the role of SI in generating mixing in river plumes.

Video shows the evolution of a rotating dense gravity current as it flows down the continental slope, undergoes geostrophic adjustment, and develops symmetric instability leading to irreversible shear-driven mixing. The top left panel is the alongshore velocity, marked by a bottom-intensified (blue) and surface-intensified (red) jet. The lower jet is formed as the dense water moves off the shelf and is deflected to the right by the Coriolis force; the upper jet is due to surface return flow that is also deflected to the right. The bottom-intensified jet is weaker due to the presence of bottom drag. The lower left plot shows the passive tracer concentration, used to track the dense shelf water as it descends down the slope through the bottom boundary and then undergoes off-slope mixing by symmetric instability. The right panels show the offshore and vertical velocities, where the signature along-front diagonal motions of the symmetric instability are evident.

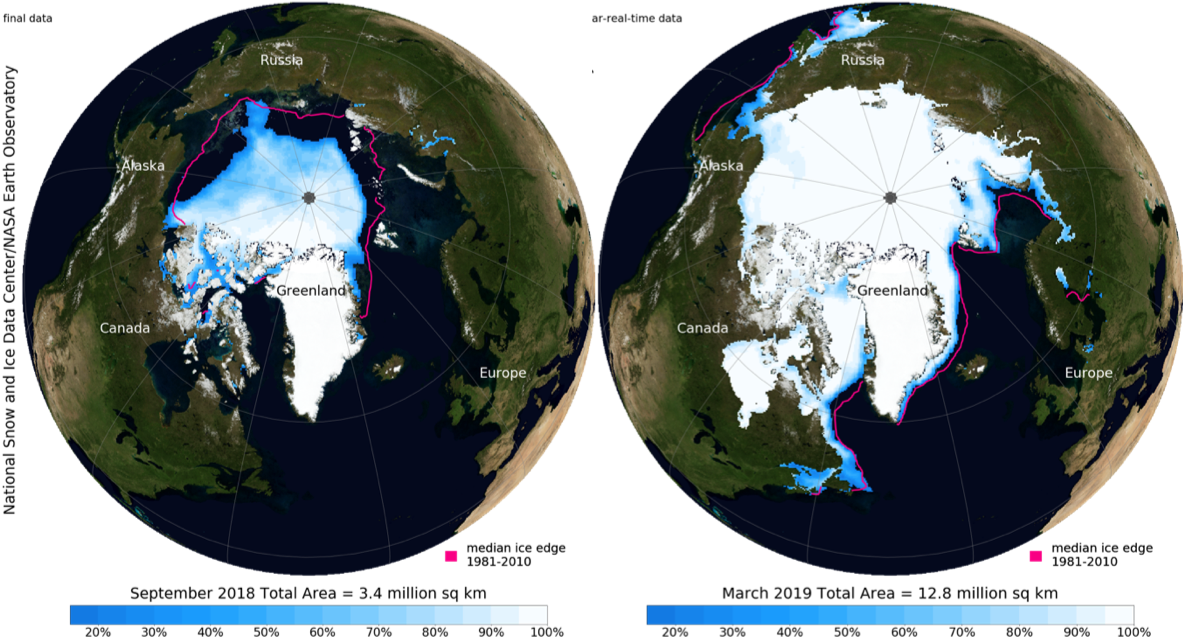

Arctic Overflows & Climate Change

The term “overflow” refers to the buoyancy-driven descent of dense water formed through cooling, freezing, or evaporation in shallow regions of the ocean, such as continental shelves and marginal seas. As dense water descends into the ocean interior, typically as a terrain-following gravity current, it undergoes mixing, entrains ambient water, and serves as a conduit for irreversible exchange and ventilation of the otherwise relatively quiescent abyssal ocean. Dense overflows feed intermediate and deep water masses including North Atlantic Deep Water and Antarctic Bottom Water, thus being substantial contributors to ocean circulation and climate.

Perhaps the most striking case of shelf overflows occurs in the Arctic Ocean, where the shallow marginal seas comprise approximately 53% of the surface area. The vast Arctic shelves are characterized by a strong seasonal cycle, with ice melting in the spring/summer months, and intense cooling with sea-ice formation in the autumn/winter months. The combination of cooling and salty brine rejection from developing sea ice leads to highly dense waters being formed in the shelves. These dense waters are among the densest in the World Ocean and ventilate the deepest portions of the Arctic. My research has focused on studying the dynamics and mixing processes that dense overflows undergo as they propagate into the ocean interior. This understanding is crucial to explaining the water mass structure of the entire basin and predicting its response to changing climatic conditions. I am also exploring the changes in dense water formation and ventilation pathways that the Arctic will experience as a result of warming.

Model Development

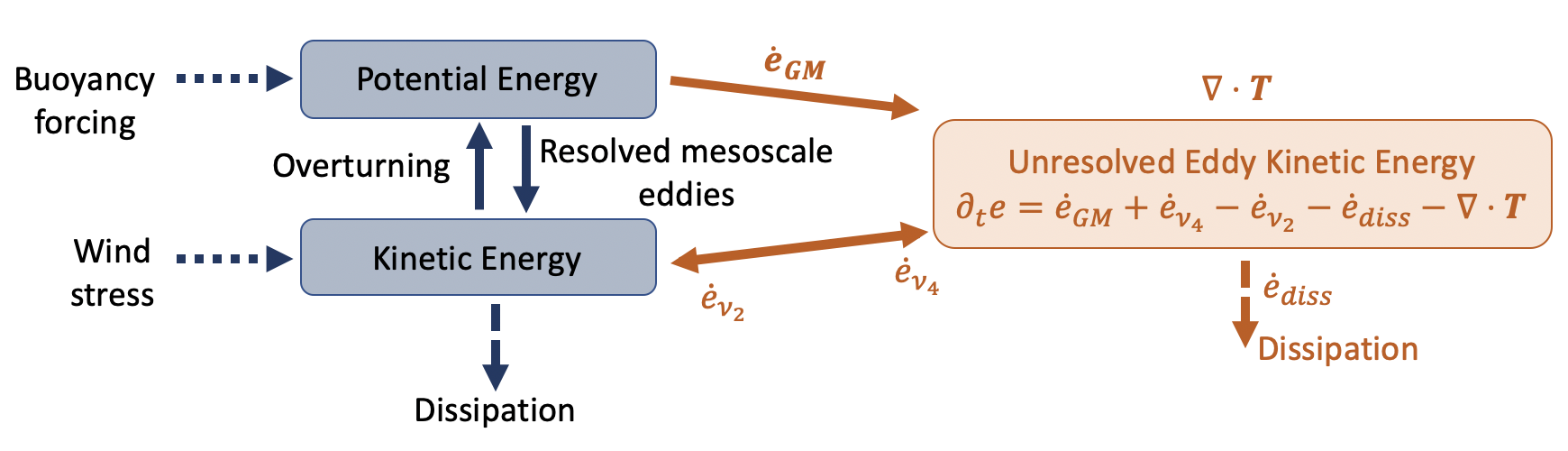

Schematic (adapted from Jansen et al. 2019) that illustrates the oceanic energy cycle and the role of unresolved mesoscale eddies therein. The interactions of the subgrid eddy kinetic energy must be parameterized in a model that does not fully resolve the mesoscales.

My graduate and postdoctoral research have both focused on studying physical processes and then deriving approaches to representing them in climate models. During my PhD research I developed a parameterization (within the GFDL-MOM6) for representing submesoscale symmetric instability in the abyssal ocean. I applied the scheme to studying dense gravity currents in the Arctic Ocean, and found that it successfully captured the mixing influences of submesoscale turbulence when not explicitly resolved.

In my postdoc research I have been focusing on improving our ability to model mesoscale eddies in modern ocean models, with a focus on representing the vertical structure influences of eddies accurately. I am especially interested in how to parameterize mesoscale eddies at resolutions that partially resolve them, a challenging regime for existing schemes.

Dynamics of Estuaries

Estuaries are dynamic locations where rivers meet the ocean. They serve as habitats for a rich breadth of species, influence coastal ocean properties, and provide significant ecological, cultural, and economic benefits. Recently I have been studying the various regimes characterizing freshwater river plumes through high-resolution numerical modeling using the nonhydrostatic MITgcm. I have focused how these freshwater plumes entrain and mix with the ambient ocean, what influences whether or not they maintain coherence as they propagate offshore, and the role of submesoscale instabilities and waves in their dynamics.

Video shows the evolution of a river plume under two regimes — with constant northward winds (left) and with no winds (right). One can note the drastic difference in the propagation and horizontal extent of the plume.